| |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

| |||||||||||

|

worksheet Long-term monitoring of white sharks (Carcharodon

carcharias) at

Executive Summary The Pelagic Shark Research Foundation (PSRF) established the Año Nuevo Island (ANI, Figure 1.) White Shark Long Term Monitoring Program in 1992. Since 1995, over 100 sharks have been tagged and identified from this site, including many resightings of animals and both visual and manual tag recaptures of long-term identification tags attached to the sharks at ANI, in addition these PSRF long-term identification tags deployed at ANI have been observed and documented at South East Farallon Islands, SEFI. The ANI White Shark Long Term Monitoring Program has also been developed to apply the most advanced means of tracking sharks as they have became available. Since 2000, pop-up archival satellite tags (PATs) have been used to study white shark migration and movements as well as infer behavioral patterns along migration routes. Most recently, during the period between September 2005 to January 2006, 18 PATs were attached to individual white sharks at ANI by the PSRF as affiliates in the Tagging of Pacific Pelagics (TOPP) program. The result has been an unprecedented amount of migration information on sharks tagged at this site. The same is being done by fellow TOPP researchers (Stanford and UC Davis) at other California sites (Tagging of Pacific Pelagics 2006). Collaborating with fellow researchers from other California white shark study sites has resulted in maximizing the potential of these tagging studies through the sharing of tag data and field identification photos. Continuation of long-term monitoring at ANI is essential to further the groundbreaking advances in knowledge that has resulted from PSRF’s efforts at ANI and those of the other teams working at the other California sites.

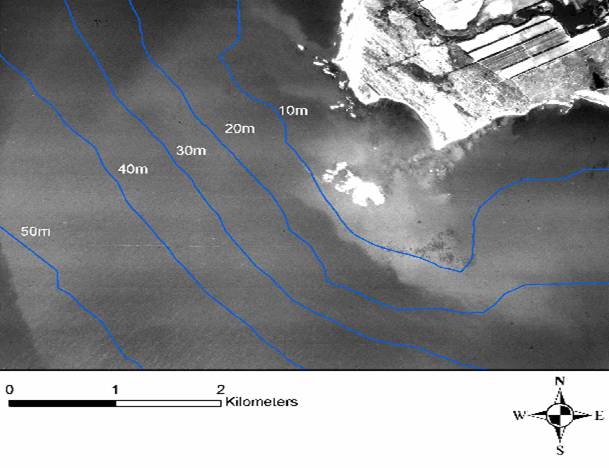

Figure 1. Introduction Despite being the most often depicted, easily recognized and popular species of sharks, relatively little is known about the natural history, range, population structure or reproductive biology of white shark. Until recently, white sharks were believed to be a primarily coastal and neritic species by the conventional wisdom. White sharks were assumed by many to spend the majority of their time in relatively close proximity to shore. Recent studies, however, suggest that these sharks in fact spend a great deal, if not the majority of their life, in open ocean waters, regularly diving to great depths (Boustany et al 2002). Historically, white sharks have been difficult to study for a variety of reasons. They are large and can be difficult to work with. They are difficult to keep alive in captivity, let alone capture and transport. They spend most of their time subsurface and they are an apex predator with a relatively small population size. Updated methods using electronic tagging technology and DNA analysis can now provide a clearer picture of the migratory behavior and population dynamics of large pelagic animals such as the white shark. Electronic pop-up satellite archival tags are designed to record pressure, temperature and light-level data when attached to marine animals. From pressure data, an animal’s depth information can be recorded, as pressure increases with depth. Light-level data, recorded from a light meter in the satellite tag, can be used to estimate local noon and/or midnight and can be used to estimate longitude of a traveling animal when compared to Greenwich Mean Time. Length of day, also recorded from the light meter, gives an estimate of latitude, as day length changes as a function of distance from the equator. Latitude and longitude data are at best accurate to plus or minus one degree. The tag can be pre-programmed to pop off after pre-designated lengths of time. After releasing from an animal a tag floats to the surface and uplinks with the Argos satellite system which downloads archived information.

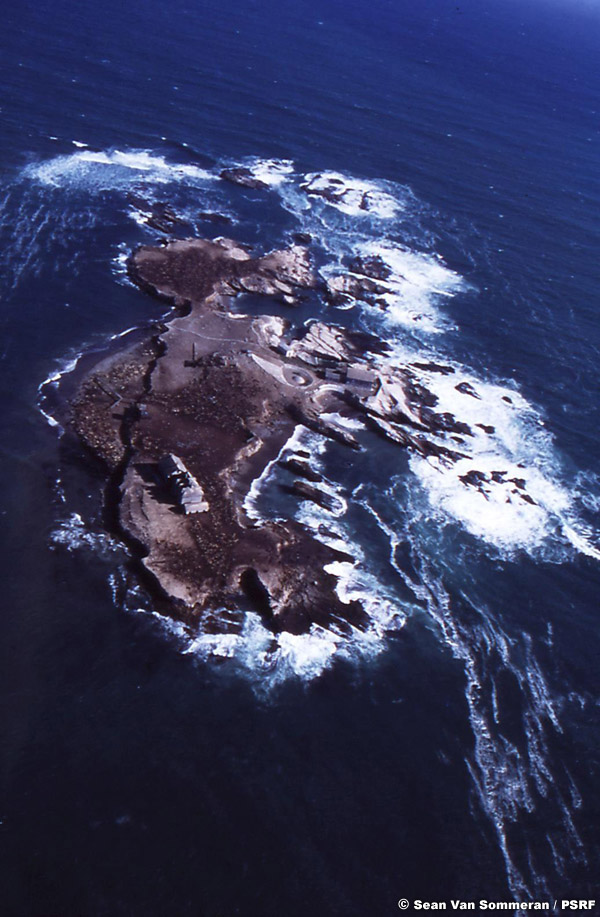

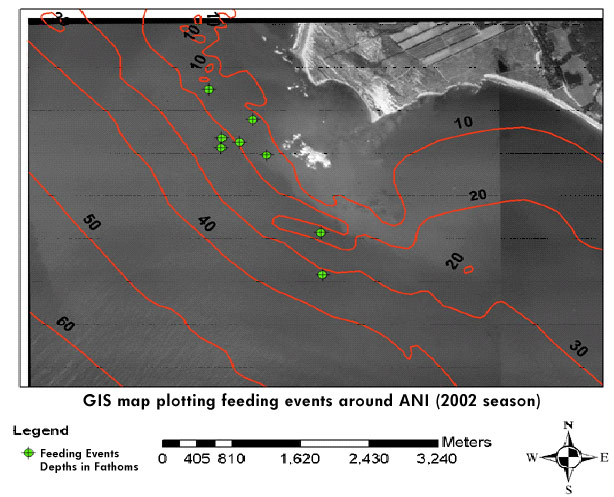

Año Nuevo Island (Figure 1), located 22 miles north of Santa Cruz, California, hosts a large pinniped population, which increases seasonally with the arrival of the northern elephant seal, Mirounga angustirostris, December-March in particular(Le Boeuf, 1985). Known to be a rookery for the elephant seal, the island is attractive to white sharks whose presence peaks in the months October-February each year. Since 1992 researchers have attempted to study white shark behavior, individual identification, social and feeding interaction, and migration, by monitoring shark presence and activity around the island. Some of the variables being studied involve where they go when they leave the study site, why and how often individuals return to the same site, where the sharks reproduce, how deep they dive and why, and are there resident sharks that stay in the area year round while others migrate thousands of miles only to return to the site at a later date, as well as general population structures and relation to other populations worldwide. The results of this and associated studies will go to help answer these questions. Aside from purely scientific interest, researching shark behavior may also be important in protecting the species as well public safety, understanding and appreciation. Field Procedures Research is conducted from a small research boats offshore from the seaward side of Año Nuevo Island (ANI) in water depths generally between 5 m-25 m. Sharks are attracted to the boat by utilizing a seal-shaped surface lure and a small portion of natural bait as an attractant. The lure, a plywood cut-out 2.4 m in length, is painted yellow on top, for easy visual tracking by observers in various sea conditions, and brown on bottom to mimic the coloration of an elephant seal. The lure is typically deployed a distance of approximately 10m to 20m from the research boat and manipulated with a heavy tackle rod and reel. Seal or whale blubber is used as bait and tied off closely to the boat. The seal blubber generates a scent corridor and visible lipid slick as the boat drifts from various positions around the island. Following the scent corridor and visible slick toward its source, sharks typically surface to inspect the entrained seal lure. As the shark closes with the lure, the rod and reel is employed to maneuver the lure and shark into close proximity with the vessel and its photographic and tagging crew. At no time is the bait presented or fed to the shark. The point of contact and relative position of each shark is plotted and logged using a GPS unit. Sharks lured to the research vessel are photographically documented, identified when possible, and characterized as to sex and generational category. When possible, sharks are documented both top-side and subsurface with digital still and video photography using fin features and scarring patterns as distinguishing keys. Using a tagging lance, individual sharks can be marked or attached with identification tags (floy/streamer tags, placard tags) and or telemetry devices. Tissue samples are acquired via an interchangeable biopsy needle.

Ultra-sonic acoustic transmitters are attached to sharks via tagging lance and tracked via underwater hydrophones linked with a shore based computer that monitors the hydrophones via VHF radio transmission. Archival satellite tags are attached to sharks and tracked via satellite and computer interface. Prior to attachment, each tag is tested for transmission and location accuracy using Satscape satellite forecast software. Attached tags record data internally for a predetermined interval. After the pre-programmed period of time, a chemical reaction within the transmitter causes the wire leader attachment to part and the tag releases from the shark and floats to the surface. Archived information is then radio-transmitted to the Argos satellite system and downloaded by researchers. Individual identification tags are attached to sharks as long term visual cues and permanent identifying markers with unique number code and return contact information. Tag series numbers, types and colors can be made specific to each location where tagging occurs. Tissue samples are taken using a lance mounted biopsy needle. Strands of tissue, collected and fixed in ethanol, are forwarded to lab scientists for DNA analysis. DNA samples have been used in kinship studies and shark conservation work (Shivji 2002). Results Tagging overview Since 1995 over 100 tags have been attached to white sharks at ANI, this includes 25 electronic satellite transmitters, 11 ultra-sonic acoustic transmitters and approximately 80 long term identification tags and two dozen DNA samples have also been gathered at ANI. One satellite tag was placed on a juvenile white shark in southern California in 2004 as well.

Many of the sharks tagged carry combinations of electronic and long term identification tags (ID tags). Long term ID tags with unique codes are used as the lanyards that fasten electronic tags to a shark and remain with the shark after satellite tags separate from the animal. These simple identification tags are useful with logging seasonal and inter-seasonal observations of previously encountered sharks for mark and recapture analysis. Long range recoveries of tags, either visually or manually recaptured from off site locations, have the potential to add immensely to knowledge of white shark migration (PSRF Website).

Long Term Identification Tags On December 26, 1995, an estimated 16.5’ TL female white shark was tagged with a floy tag at ANI. Almost six years later, on October 28, 2001, the same large female was seen at ANI and the tag from 1995 was manually removed from the animal. The shark was estimated in 2001 to have reached 18’ TL and was retagged and photographed for future identification purposes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Algae covered streamer tag #P0311 emplaced 26 December 1995 and recovered

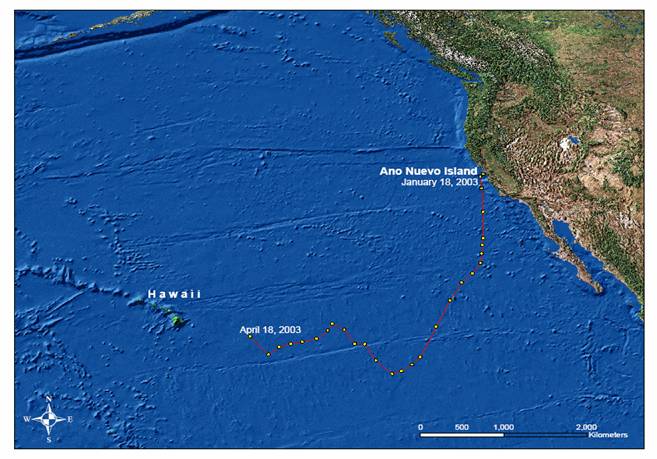

28 October 2001. Although it is not uncommon to have individual sharks return to the same site over different seasons, the recovery of the floy tag from ANI in 2001 verifies observations that sharks may return to a site over long periods. In this case it was nearly six years between confirmed sightings. Acoustic telemetry tags During the periods 1997-1999 the PSRF collaborated with UC Davis researchers in attaching 11 ultra-sonic acoustic transmitters to white sharks at ANI as well as assembling and deploying and operating a stationary hydrophone array and island based computer/VHF Interphase system for live time tracking of numerous white sharks simultaneously as well as archiving the data and plotting movements in proximity to the island and associated seal colony. Two manuscripts were published in the journal Marine Biology and coauthored by PSRF staff, A. Peter Klimley being Principal Investigator. Satellite tags In Fall/Winter of 2000, the PSRF purchased and deployed four archival satellite transmitters onto white sharks at ANI. The effort resulted in revelational data that verified PSRF theories that the white sharks were in fact spending considerable time offshore and at depth. This same year Stanford researchers working at SEFI provided evidence of a trans-Pacific migration to the Hawaiian Island chain. In 2002, a paper entitiled ‘Expanded Niche for White Shark’ was published in Journal Nature (Boustany, et al.) that included PSRF’s year 2000 ANI data. In 2003, four more transmitters (tags) were deployed by PSRF on individual white sharks at ANI. Three of the tags were successful and transmitted additional data back through the satellite uplink. Of those, all three sharks traveled south-west along the East coast with one of the sharks eventually taking a westerly track towards the Hawaiian chain after reaching 26 degrees north latitude. According to the tracking data the route taken from point A to point B covered approximately 1800 nautical miles in three months, including a stretch in which the shark covered approximately 400 nautical miles over a three day period. (Figure __)

Figure __. Three month satellite track from a

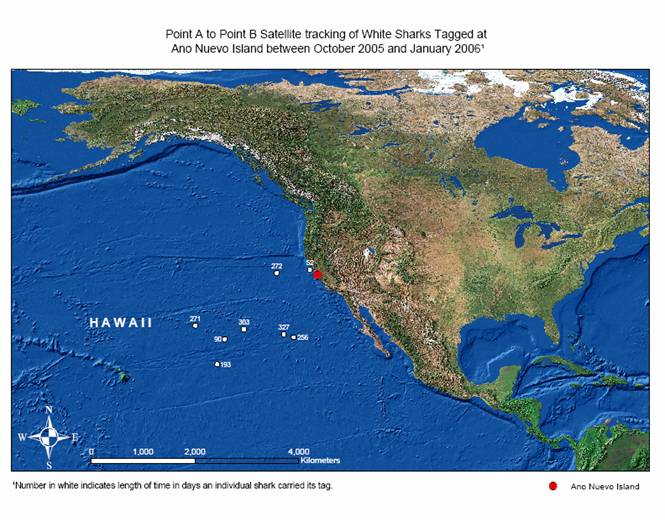

white shark tagged at For the 2005-06 season PSRF joined efforts with Stanford’s TOPP program to increase that efforts sample size and range of the satellite tagging program and to share past knowledge and experience with fellow and affiliate shark researchers and the general public. A total of 18 tags were attached to white sharks at ANI over the period September 11, 2005 through January 21, 2006. Most transmitters attached were programmed to stay on the shark, archiving data, for at least nine months. Because of the longer duration tags were placed on sharks, a clearer picture of shark white shark migration has resulted. Data is preliminary, however all tracked animals so far have migrated to the mid-pacific open ocean between California and Hawaii (Figure__).

Figure__. Preliminary Point A to point B data for 8 of the 18 sharks tagged with

satellite transmitters at ANI between September 11, 2005 and January 21, 2006. In addition to location data, satellite pop-up archival tags are equipped with a pressure sensor that can be used to log depth for the duration of the track. Depth data is an important topic in white shark research as relatively little has been known until the recent advent of electronic instrument tagging. In fact, from data received from tagging studies at ANI, sharks spend a considerable amount of time at depth, sometimes as deep as 275 meters (Figure__). The shark tagged in 2003 (Tag #39326) that tracked out towards Hawaii from ANI spent considerable time repeatedly diving and surfacing along the way as can be seen in the histogram in Figure__ and the three dimensional tracking/depth representation in Figure__. Shark #39326 showed a trimodal depth preference during its offshore phase alternating time at the surface, approximately -80 meters and approximately -160 meters. Comparison of depth data between different sharks tracked will be an important part of understanding shark migration and behavior. Insights gained from diving patterns between sharks may ultimately give us insights into to what drives such diving behavior.

Figure__. Depth histogram showing

the three month dive profile of a white shark satellite tagged at ANI.

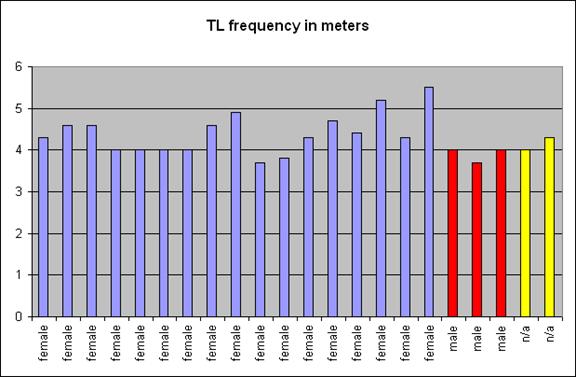

Of the most important aspects of the white shark study are field observations and documentation. Behavioral observations, sex and generational categories, predation and prey selection, population structure and individual identification are all aspects of white shark life history that can be documented in the field during peak shark presence at the study site. Much of the year it is not possible to observe sharks in the wild so it is extremely important to spend as much time as possible observing sharks when they are in the inshore phase of their migrations. Population Structure At ANI there is a pattern of a high female to male ratio (Figure__). Average size TL of females to

males (Figure__).

Figure__. Sex ratio observations of white sharks tagged at

ANI from 1995 through 2006. Gender Graph/Population Structure:

There is an apparent relative abundance of female white sharks, mostly sub-adult and Adult specimens, (Figure__). Smaller sharks are comparatively rare. Predation and Prey Selection Predatory events have been observed at the study site since 1992.

Pinnipeds. Otariids-

Phocids-

Predations upon northern elephant seals at Año Nuevo Island are typically initiated subsurface, often enough resulting in an injured or dead seal ultimately floating or fleeing to the surface. -Pecking order observation following feeding event Identification of individual sharks is the first step that has been taken to try and ultimately make assessments about population size and migration/residency patterns in a data poor situation. Multiple methods have been used to identify individuals at ANI, including photographic indexing of dorsal fins and unique identifying marks. To date a photo library containing individual sharks identified over more than one season has been created and is available at: pelagic.org/archive/ID_pics/index.html (example Figure__ 2) Photo IDs same shark different season). Used in conjunction with the different tagging and tracking studies, photo ID greatly enhances the ability of researchers to recognize individuals in the field and in each subsequent season as well as providing as basis b which the individual sharks may be recognized and documented by other researchers at other sites. In 2000 large visual ID, or placard, tags were introduced into PSRF’s methodology to offset the difficulty of manually recovering floy tags from sharks. Placard tags are approximately six inches in length and two inches wide and have a bold typeface number visible on both sides. These tags are easier to see underwater and a “visual” recapture of a tag is synonymous with pulling off an algae covered streamer tag from a shark, although much easier. To date placard tags have been attached on white sharks at ANI, as well a number of them have been placed on white sharks in Southern California and Guadalupe Island offshore from Mexico. It is the intent of this type of tagging that researchers in other areas of the Pacific will someday give reports of sighting tags that PSRF has emplaced at ANI, Southern California or Guadalupe Island. Continuing to collaborate with TOPP researchers will make huge inroads into knowledge about white shark populations through broadening the range of areas in which these sharks are studied as well as sharing of data and looking for patterns in behavior in sharks from different areas with similar oceanic conditions.

Sketch:

Acoustic study----general overview----Klimely’s paper-----general results/conclusions.

1992-1995 pilot study – boat Ops, Island occupation, observation/experimental-observing predation.

1995-1997 ID tagging, observation/predation documentation, photo ID.

1997–1999 acoustic tracking, photo ID.

2000 deployed 4 sat tags – offshore theory verified. ID photo, predation documentation.

2001-2003 ID tagging, Sat tag tagging, DNA sampling, tag recovery, predation, documentation.

Outline topics:

-size

-sex segregation

-trends

-good years/bad years

-location of sightings rel to ANI (i.e. So or No)

-Tracking

-depth patterns

-deepest

-duration

-Feeding events

-recaptures

-visual

-2001 manual recovery

-Dorsal/etc. ID shots

-definite matches across years

-Attach ppt here? Is this possible? Or figures

Effort table example:

FIGURE EXAMPLES/IDEAS

GRAPH 1

Average # sharks seen/sample day

GRAPH 2

Average # sharks seen/sample season (year)

GRAPH 3Average TL of sharks seen by year and sexFIGURE 3

Point A to Point B tracking of all white sharks tracked by PSRF through 2004.

Point A to Point B tracking of 2005-2006 TOPP sharks (2 Microwave)

Discussion:

-Tracking

-effects on ability to get Lat/Long data when shark is deep

-Recaptures

-Difficulties in recovering floy tags. New innovations.

Mark and recapture…goal…population size generalization.

-Advances in computer based tagging technology

References:

Teo, et al

Klimely

Boustaney

Shivji

|

| |

[ home ] | [ contact us ] | [ support us ] | [ shop ] | © Copyright 1990-2006 PSRF All rights reserved. |

Site development by |