FIELD OBSERVATIONS AND TAG RECOVERY FROM A WHITE SHARK (CARCHARODON CARCHARIAS) AT AÑO NUEVO ISLAND, CALIFORNIA

SEAN VAN SOMMERAN, CALLAGHAN FRITZ-COPE, SCOT LUCAS

Pelagic Shark Research Foundation

www.pelagic.org

psrf@pelagic.org

An identification tag that was attached to a white shark at Año Nuevo Island, Northern California in December 1995 was later recovered from the shark at the same site in October 2001. Although previously tagged sharks are observed by researchers at the site every fall and winter, this was the first such tag recovery from a white shark from the Eastern North Pacific. Field observations are included and recommendations for tag improvement are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

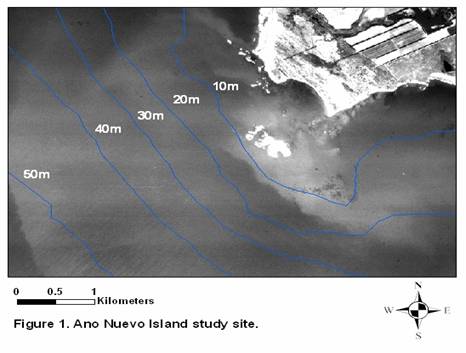

A long term monitoring program studying white sharks was established in October of 1992 at Año Nuevo Island California (Figure 1), by the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation. Beginning in fall of 1995, white sharks were photographically identified and tagged with permanent ID tags. The study also involves telemetry and tissue collections in conjunction with behavior observations. Sharks are tagged in an effort to study the movements, range and population structure of white sharks. The sharks are brought to a drifting research boat with the use of a pinniped shaped lure and a small amount of pinniped bait and/or by researchers closing with ongoing predatory events whereby the sharks are surface feeding on natural prey.

STUDY AREA

The research site off Año Nuevo Island is situated approximately 22 miles up coast from the Santa Cruz Harbor and approximately 56 miles southeast of the Farallon Islands. Its location sits within the boundaries of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Año Nuevo Island and its adjacent mainland point are a state and federal preserve encompassing one of the world’s largest mainland rookery (LeBoeuf, 1981) for the northern elephant seal, (Mirounga angustirostris).

METHODS

Research is conducted from a small boat offshore from the seaward side of the island in water depths of between 5 m-25 m. Sharks are attracted to the boat by utilizing a seal-shaped surface lure and a small portion of natural bait as attractants. The lure, a plywood cut-out 2.4 m in length, is painted yellow on top, for easy spotting by observers, and brown on bottom to mimic the color of an elephant seal. The lure is deployed a distance of approximately 10m from aft the boat and is tethered to a fishing pole aboard the vessel using high-test fishing line. The bait is tied off directly aside the stern section of the boat. The bait is neither presented or fed to the sharks. In general, a scent corridor, or slick, is created by introduction of the lipid saturated bait into the water as the boat drifts across the seaward sides of the island.

Following the scent corridor toward its source, sharks usually surface to inspect the preceding lure before eventually approaching the boat. Naturally occurring shark predations on pinnipeds are opportunistically utilized by researchers and carefully approached, when possible, to attach tags to sharks. Sharks are tagged with number and color coded identification tags attached to the end of a tagging lance. Each tag number is unique for future individual identification. Lengths of sharks are estimated in comparison to the known lengths of the seal shaped lure, and that of the research vessel used each sampling day. Locations of shark activity are documented by using a GPS unit and notes are taken as to location relative to Año Nuevo Island.

OBSERVATIONS

On 26th December 1995, a predatory event involving a white shark on an elephant seal was observed off of the northern end of the island in approximately 20 m of water at 10:10 am PST. The seal was a dying adult female with massive injuries to the lower jaw, neck and chest. A large shark appeared and seized the convulsing seal and carried it a short distance before removing a bite. The shark was an estimated 5 m TL female white shark which was tagged with a white plastic streamer tag with serial number P0311 (Fig.2).

Figure 2. Idnetification tag #0311 attached 26 December 1995 and

recovered 28 October 2001.

The seal, was completely consumed within 40 minutes by shark P0311 and another shark, estimated to be 3.5-4 m TL. Both sharks were tagged during the feeding event and were seen repeatedly during the remainder of the 1995-1996 season. A total of 12 sharks were tagged during late October 1995 and late December 1995.

On 25 October 2001, a white shark made contact with the seal shaped lure off the NW end of the island in approximately 15m of water. The force of the contact made by the shark on the lure caused the plywood lure to split in half. The shark was an adult female estimated to be in excess of 5.5 m TL. The animal was tagged with a yellow, plastic California Department of Fish and Game streamer tag with serial number #18903 and was photographed for archival identification. It was then observed that the animal carried a previously attached, algae covered tag, in addition to the newly emplaced tag.

Three days later, on 28 October 2001, from a position of 37°06.21’N-122°20.40’W, an elephant seal was observed on the distant surface north west of the red bouye at 10:35 am. The seal was behaving oddly and some birds were gathering above it. The seal dived away but was seen again a few minutes later approximately 100 meters away from its previous position. At approximately 10:50 am, a large splash and the thrashing tail of a large shark were observed in the area where the seal was last sighted. As the commotion continued in the distance, many birds began to actively gather over the disturbance. In response, the research team abandoned its drift and the predation was carefully approached for closer observation and documentation.

Upon arrival at position 37°06.56’N -122°20.97’W, the seal was observed to be alive, possibly in shock, resting at the surface with its nose pointed up. It was noted that the seal was an large adult female. The seal had been bitten badly on the face and neck, and appeared to have been bitten more than once, creating a blood red slick on the surface. At times the seal would lower its head and peer around beneath the surface, presumably in an effort to orient itself in a defensive posture relative to the sub-surface shark.

After approximately 12-15 minutes, the seal grew listless and came to a rest in a horizontal position on the surface and seemed to expire at approximately 11:10 am. Visual examination of the injuries sustained by the seal at that time included some small lacerations on the left hind flipper, in addition to the aforementioned upper body injuries to the head and collar region. The lower jaw appeared to have been fractured, with the apparent mortal injury inflicted on the neck region below the broken and exposed lower jaw bone. It appeared that the seal had been hit numerous times and may have been actively attempting to fend off these assaults when first observed diving and resurfacing around 10:35 am.

At approximately 11:15 am a large female white shark, estimated at 5.5-6m TL, surfaced and removed a large bite of its prey. From a position of 37°06.67’N -122°21.50’W, the shark made a close pass near the boat. In passing, the shark was recognized as the same shark that broke the lure and was tagged with streamer tag #18903 three days earlier. The shark appeared to have several fresh injuries to its face and a set of obvious seal bites on one side of her peduncle, in addition to extensive older scars which had long since healed over. As the shark gripped the seal for another bite, it pushed the dead seal toward, and eventually against the side of the boat. It was at this time that the older, algae covered tag #P0311, mentioned previously from 31 December 1995, was manually recovered from the base of the dorsal fin. The newer, California Department of Fish and Game tag #18903 was still visible and firmly attached. Over the course of several leisurely passes the shark consumed an estimated 225-275kg of the expired seal.

At approximately 11:32 am a second large shark was observed to approach and grab the seal at position 37°06.79’N-122°21.50’W. This second shark, an untagged female, was estimated at 4.5m TL. At approximately 11:50 am and position 37°07.40’N-122°21.77’W, a third shark was observed cruising the slick left by the carcass. Shark number three was an estimated 4 m long female and also untagged. By this time the first two sharks were no longer present. At approximately 12:05 pm and position 37°07.52’N-122°21.81’W, the fourth shark of the day was detected. This animal was an estimated 4 m in length and was previously encountered on 26 October 2001. Shark four consumed the remaining 70-90kg of elephant seal. With no further shark contact, trolling effort was suspended for the day at approximately 12:50 pm.

DISCUSSION

Every season previously tagged sharks are observed at Año Nuevo Island. In the period between 1995 and 2005, over 100 white sharks were tagged and transmittered at this site. While it has been known that some individual white sharks have shown a tendency to return repeatedly to certain areas on the west coast, (Klimley, 1996) it is noteworthy that individual white sharks may revisit these sites over a substantial period of time. White shark tagged by PSRF researchers at Año Nuevo Island have also been documented at by researchers at South East Farallone Island.

The large female in this observation grew an estimated .6m (2feet) over the approximately six year period between the initial encounter in 1995 and her return in 2001. It was interesting to note the prey item was an alert adult.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Benefits of permanent ID tags include relative ease of emplacement, affordability of materials, and long lifetime of the tag itself. ID tags are limited by the difficulty of tag recovery and by the small, albeit important, amount of data produced. Innovations such as placard tags with large numbers that are legible from a short distance without recovery are currently being used to offset the difficulty of having to recover the tag itself.

By logging the number of sharks encountered each sample day and the number of animals carrying previously emplaced tags, insights into population size may be generalized, especially when data is collected and analyzed for comparison over several seasons. With this in mind, it is important to continue this part of an integrated long-term monitoring program, the hypothesis being that given a certain K-selected population, such as C. carcharias, eventually sightings of non-tagged animals should start to diminish.

All work was carried out on California Department of Fish and Game Scientific Research and Collecting Permit 801148-01 and Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary Research Permit MBNMS-20-1999.

LITERATURE CITED

Le Boeuf, B.J. 1981. Mammals. Pages 187-325 in B.J. Le Boeuf and S. Kaza, eds. The natural history of Ano Nuevo. Boxwood Press, Pacific Grove, Ca. 425pp.

Le Boeuf, B.J., M. L. Riedman, and R.S. Keyes. 1982. White shark predation on pinnipeds in California coastal waters. Fish. Bull. 80:891-895.

Klimley, A.P. and S.D. Anderson. 1996. Residency patterns of white sharks at the South Farallon Islnads, California. Pp. 365-374 in Klimley and Ainley (1996).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank D. Casper from UCSC, D. Ventresca and R. Lea from California Department of Fish and Game, as well as B. Wright from Alaska Fish and Wildlife Service for their valuable comments and encouragement; as well we'd like to thank Scott Anderson who documented the presence of a PSRF tagged white shark at SE Farallone Islands.